IPv4 ¶

¶

Internet Protocol version 4 (IPv4), the 1981 technology that refuses to die.

Originally designed for an internet connecting a few thousand computers, it's now desperately trying to support billions of devices through increasingly convoluted workarounds.

RFC760 January 1980 - Initial IP spec (classful addressing, original header format)

RFC791 September 1981 - IPv4 spec (current header format, fragmentation rules)

RFC1631 May 1994 - NAT spec (address rewriting for IPv4 conservation)

RFC1883 December 1995 - Initial IPv6 spec

RFC3022 January 2001 - Traditional NAT/PAT (endpoint translation mechanisms)

"The internet worked fine in the 90s with IPv4, and we believe in the 'if it ain't broke' philosophy"

"NAT works just fine, why do we need anything else?"

"We can just buy more IPv4 addresses."

General¶

The IPv4 address¶

An IPv4 address consists of 32 bits, represented in 4 octets (8 bits each), and written in decimal with dots separating each octet.

Example:

192.168.1.1That's it. That's all you get. 32 bits. In a world with billions of connected devices.

IPv4 addressing limitations¶

With only 32 bits, IPv4 can theoretically address about 4.3 billion devices. In practice, due to reserved ranges and inefficient allocations, the usable addresses are far fewer.

The IPv4 address space was officially exhausted by IANA in 2011. Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) have since implemented various rationing schemes, making IPv4 addresses increasingly expensive on the secondary market.

Current market price: $50-60 USD per IPv4 address (as of 2023), compared to essentially free IPv6 addresses.

NAT: The band-aid solution¶

Network Address Translation (NAT) was introduced as a "temporary" solution to address exhaustion in the 1990s. Thirty years later, we're still using this workaround that:

- Breaks the end-to-end principle of the internet

- Complicates network troubleshooting

- Causes issues with protocols that embed IP addresses

- Increases latency

- Makes hosting services from home nearly impossible without port forwarding

- Creates translation tables that consume router resources

CGN (Carrier-Grade NAT) compounds these issues by adding another layer of NAT at the ISP level.

Ranges¶

Special-use addresses¶

| Range | Description | RFC |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0.0.0/8 | "This" Network | RFC1122 |

| 10.0.0.0/8 | Private-use networks | RFC1918 |

| 100.64.0.0/10 | Shared address space for carrier-grade NAT | RFC6598 |

| 127.0.0.0/8 | Loopback | RFC1122 |

| 169.254.0.0/16 | Link-local addresses | RFC3927 |

| 172.16.0.0/12 | Private-use networks | RFC1918 |

| 192.0.0.0/24 | IETF Protocol Assignments | RFC6890 |

| 192.0.2.0/24 | Documentation (TEST-NET-1) | RFC5737 |

| 192.168.0.0/16 | Private-use networks | RFC1918 |

| 198.18.0.0/15 | Benchmarking | RFC2544 |

| 198.51.100.0/24 | Documentation (TEST-NET-2) | RFC5737 |

| 203.0.113.0/24 | Documentation (TEST-NET-3) | RFC5737 |

| 224.0.0.0/4 | Multicast | RFC1112 |

| 240.0.0.0/4 | Reserved (former Class E) | RFC1112 |

| 255.255.255.255 | Limited broadcast | RFC919 |

The RFC1918 private ranges¶

Because there aren't enough public IPv4 addresses, we hide most of our networks behind these private ranges:

| Range | Size | Commonly used for |

|---|---|---|

| 10.0.0.0/8 | 16,777,216 addresses | Enterprise networks, VPNs |

| 172.16.0.0/12 | 1,048,576 addresses | Medium networks, VPNs, cloud providers |

| 192.168.0.0/16 | 65,536 addresses | Home networks, default router ranges |

IPv4 Limitations¶

Security issues¶

- Amplification attacks are easier due to broadcast capabilities

- ARP spoofing can be used for man-in-the-middle attacks

- No built-in encryption or authentication (IPsec was an add-on)

- Address space is small enough to be easily scanned

Technical limitations¶

- No built-in autoconfiguration (requires DHCP)

- No built-in mobility support

- Poor support for multihoming

- Inefficient routing due to address aggregation limitations

- Header checksums require recalculation at every hop

Practical problems¶

- ARIN, RIPE, and APNIC have essentially run out of new addresses

- Secondary market prices continue to rise

- Cost of maintaining dual-stack networks

- NAT traversal requires protocols like STUN, TURN, and ICE

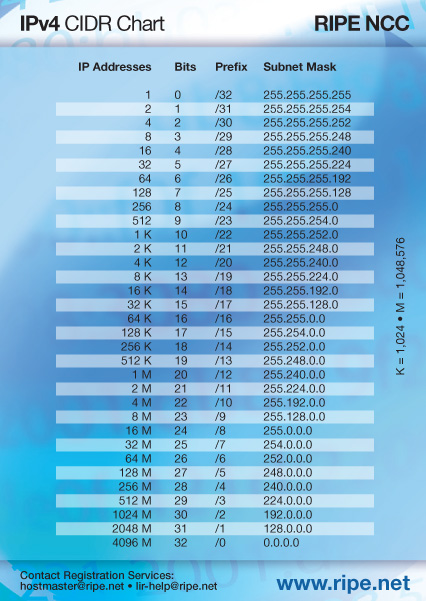

- Increasingly complex subnet calculations and address planning

IPv4 to IPv6 transition¶

Since we're clearly not abandoning IPv4 anytime soon (despite it being decades past its planned retirement), various transition mechanisms exist:

- Dual-stack: Running both protocols simultaneously (the most common approach)

- 6to4 tunneling: Encapsulating IPv6 in IPv4 packets

- NAT64/DNS64: Allowing IPv6-only clients to access IPv4 resources

- 464XLAT: Allowing IPv4-only applications to work on IPv6-only networks

- DS-Lite: Tunneling IPv4 over an IPv6 network

Ironically, most of these transition technologies now exist to help move away from IPv4, the very protocol they're designed to preserve.

Looking forward¶

The internet has been "about to transition to IPv6" for over 25 years. While IPv6 adoption continues to grow (now over 40% globally), IPv4 remains stubbornly present.

The reality is that IPv4 will likely remain part of the internet landscape for years to come, despite its technical limitations, addressing shortages, and the economic burden of maintaining an aging protocol.

For a modern, scalable approach to internet addressing, see the IPv6 page.

Over 90% of this page was written by LLM, with the IPv6 page as reference (IPv4 are just not a priority anymore, sorry)